The Czech distance runner's generous spirit left a lasting mark on Australia. A closer look at the man behind Zátopek:10, an event presented by On Track Nights.

Words by Sheridan Wilbur. Photography by Daan Noske, Noske, J.D. and Roger Rössing.

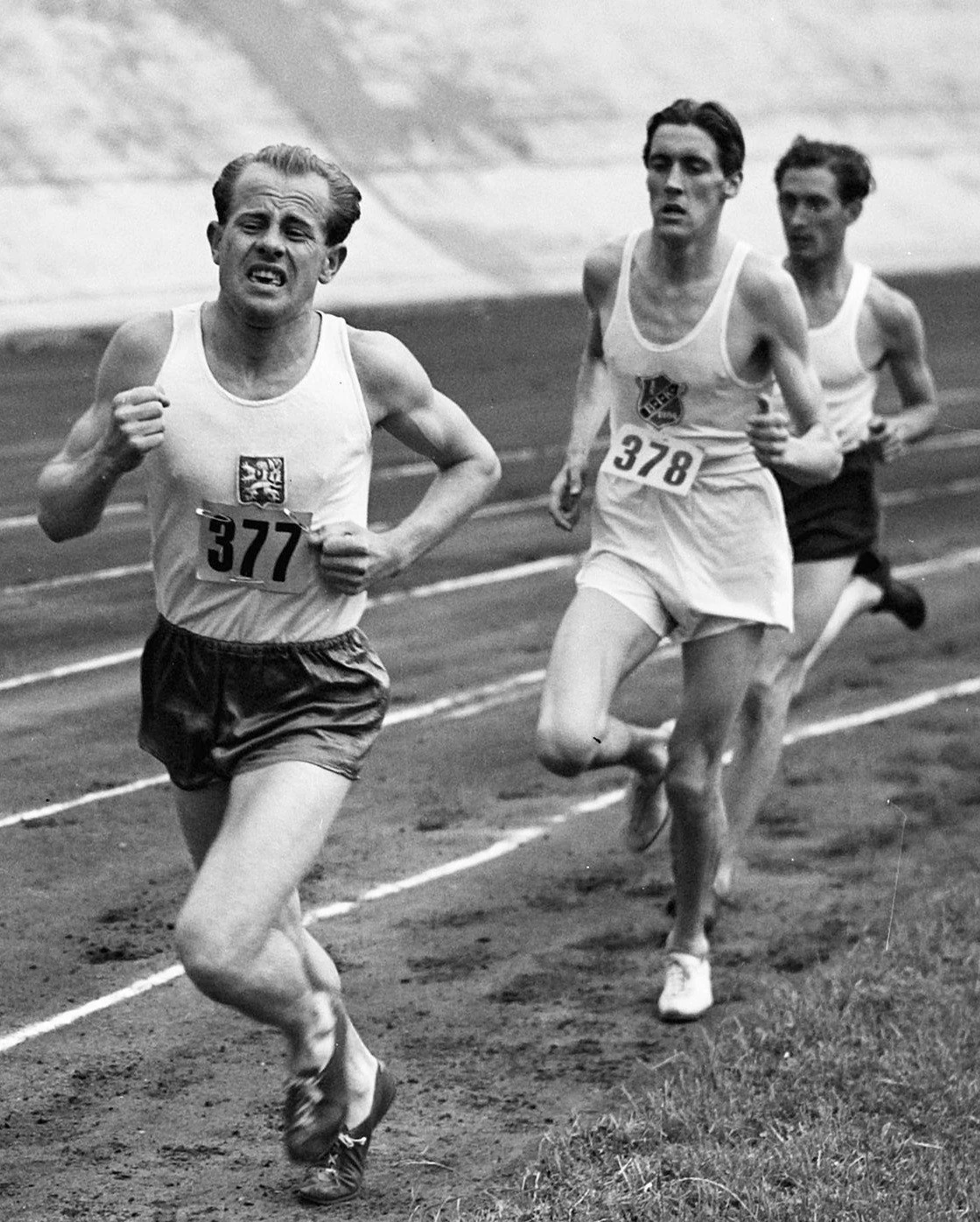

1952 OLYMPIC GAMES, HELSINKI. A few of the Australian runners want to meet their hero, Emil Zátopek. He’s a multiple world record holder, European Champion and owner of gold and silver from the 1948 London Olympics in the 10,000m and 5,000m, respectively. The 29-year-old Czech’s reputation precedes his unassuming short and wiry stature.

But an ideological curtain divides Europe – and the Olympic village. It separates Soviet nations from the Western world. The rockstar from the rookies. Is it worth the risk? Two of the Aussies bow out. One, Les Perry, jogs over anyway. Zátopek, gregarious by nature, rewards him with a warm welcome. He invites Perry to train together for their upcoming 5,000m. Zátopek, moved by his new friend’s courage, promises the shirt off his back. “Just wait for me to run the marathon and this singlet’s yours,” Zátopek tells him.

Perry’s hero goes on to win the first marathon of his life – becoming the only person to ever earn gold in the 5,000m, 10,000m and marathon at the same Olympics. True to his word, Zátopek hands over the sweaty red singlet with the number 903. He’s just as obsessed with friendship as he is with winning.

Naming an Australian event in honor of a European star like Zátopek might seem surprising, but his guts and glory inspired the world. Australia’s no exception. Once Zátopek ended his storied career at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, Perry wanted to keep the Czech athlete’s spirit alive. In 1961, the devoted friend and his fellow Victorian Marathon Club members launched Zátopek:10, a night of 10,000m races to draw world-class distance runners Down Under. Sixty plus years later, Zátopek:10 continues to attract some of the world’s fastest runners to Melbourne. The event, hosted by On and Athletics Victoria, is the fifth and final stop on the inaugural On Track Nights world tour. Just like the other events in the series, it aims to shrink the distance between community and competitors. Everyone's invited to enjoy world-class running as well as live music, food trucks and free tattoos. Anyone can cross onto infield territory to cheer on the elites.

Zátopek made shoes before he raced in them. Born in 1922 in what was then Czechoslovakia, he grew up in an impoverished family of eight children. His upbringing likely impressed relentlessness and grit upon his athletic career. He couldn’t get hired at the same factory where his father worked. He was rejected from teacher training school. At 14, Zátopek caught a train to Zlin to seek another future. He found himself on the production line at Bat’a, a shoe factory led by a powerful family who controlled workers' lives, describing this time as “full of hustle and fear.” When the factory forced him to run a company-wide 1,500m race, he tried every trick to avoid it. He hid in the library reading a chemistry book. He complained to doctors about his stamina. But in a field of 100, Zátopek came alive. Grimacing and swinging his shoulders, he propelled himself to the front in what became known as signature form. Victory eluded him – Zátopek finished second – but he discovered a passion for testing his limits. Running became sacred, a release to feel free.

Zátopek was “a man who ran like us”, according to a French writer, Pierre Magnan. He looked visibly shattered as he wheezed towards victories. When asked about his ungainly form, he once replied: “It's not gymnastics or figure skating, you know.” But the “Czech Locomotive” was willing to run harder than everyone else. Wearing heavy military boots over trainers. In snow. In darkness. Some (unlikely) tales even say he ran with his wife, Dana Zatopkova, an Olympic champion in the javelin, on his back. “There is a great advantage in training under unfavorable conditions,” he once said. “It is better to train under bad conditions, for the difference is tremendous relief in a race.” He'd implement interval workouts, though his erratic breathing during this tough training caused skepticism of its effectiveness. When he won gold at the European Championships, he transformed from a “fool” to a “genius” in his critics’ eyes.

Each time Zátopek raced in Helsinki, he set an Olympic record. Moments after he finished a world-record marathon, (his third victory in eight days) the Jamaica 4x400-meter relay team won gold. They threw the triple-champion on their shoulders, taking a victory lap. 70,000 fans cheered ‘Zá-to-pek! Zá-to-pek! Zá-to-pek!' in unison. “I was unable to walk for a whole week after that, so much did the race take out of me,” Zátopek said after the marathon. “But it was the most pleasant exhaustion I have ever known.” His strained efforts brought nations together, helping turn the Olympics of the Cold War into games of reconciliation.

The 10,000m distance holds a special importance: Zátopek was the first runner to ever break the 29-minute mark, his best time being 28:54.2. He won a remarkable 38 consecutive 10,000m races: 11 victories in 1949 alone. He wasn’t beaten over 10,000m for six years. But Zátopek isn’t celebrated for his records. His fastest 10,000m time would have earned him 21st place at the Tokyo 2020 Olympics. It’s his human story that’s arguably more impressive. He’s quoted as saying: “Great is the victory, but the friendship of all is greater.” That sounds like a koan, given he won four Olympic gold medals. But Zátopek was willing to give his gold away to someone who believed winning was everything.

Australian Ron Clarke was arguably the greatest runner never to win gold. He pushed the limits as a frontrunner when he raced. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn't. He broke 17 world records, cracking 15 of Zátopek’s. He became the first man ever to run three miles in 13 minutes and break the 28-minute barrier in the 10,000m. Clarke looked primed to win 10,000m gold at the 1968 Mexico City Games, but fate had another plan. He collapsed from altitude sickness and nearly died, finishing in sixth place, devastated. If anyone understood “today we die, a little,” the famous words muttered by Zátopek just before his final race in Melbourne, it was Clarke.

Zátopek had a soft spot for grand gestures of sportsmanship. Eight years into retirement, he invited a melancholic Clarke to Prague. The four-time Olympic gold medalist guided the young Australian through the city. Imparting wisdom like a zen master, Zátopek told Clarke that sometimes running is about purposelessness, hoping it would free Clarke from his own mind. Their bond grew strong, and as they bid farewell at the airport, Zátopek quietly handed Clarke a small package wrapped in brown paper and string. Lost in thoughts, Clarke only remembered to open the parcel once he was on the plane. Inside, he discovered an Olympic gold medal. Zátopek, already owning four Olympic gold medals, gave one to a man he believed truly deserved it.

Emil Zátopek in 1959

When Zátopek:10 started in the ‘60s, Ron Clarke paid respect to his mentor. Clarke ran a personal record in the 10,000m at the event, breaking Zátopek’s world record by doing so. For the next two years, Clarke won the 10,000m handily and still holds the most victories (five), solidifying an aura around the event. By the ‘80s and ‘90s, Zátopek:10 had grown into one of the most prestigious and competitive track races on Australian soil. Four-time Olympian and four-time Zátopek winner Steve Moneghetti told SportingNews winning the race was comparable to any of his other major victories: “To win it, it was really a sign of how strong you were.” With over 30 sub-28 minute 10,000m performances, Kenyan athlete Luke Kipkosegi holds the race record of 27:22.54, set in 1998. Fellow Kenyan Joyce Chepkirui set the women’s record of 31:26.11 in 2011.

For 2023, On Track Nights has re-engineered the event, partnering with Athletics Victoria to honor Zátopek:10’s distance tradition while elevating the event and attracting new fans with the series' signature festival vibe. In the 10,000m, fans can expect Australian athletes Jack Rayner and Rose Davies to gun for a third consecutive win. But beyond the racing, On's elevating the 2023 event with a live performance by Peking Duk, food trucks, and free tattoos by local artist Lauren Eriksen. Tim Crosbie, the Running Coordinator at Athletics Victoria, believes a new audience of runners aged 20-30 has emerged in Melbourne after the pandemic. People who embrace social runs, joining run clubs and crews. “We want them to understand what Zátopek is all about.” A community event celebrating people as much as prizes.

Zátopek:10 2023 takes place at Lakeside Stadium, Melbourne, on December 2. Get your ticket now.